For nearly five centuries after the Buddha’s passing, his teachings were preserved solely through memory. Monks would chant the sutras together, passing them down from teacher to student in an unbroken oral lineage. However, in the 1st century BC, a crisis in Sri Lanka threatened to break this chain forever.

The Crisis of Oral Tradition

During the reign of King Valagamba, the island was ravaged by a twelve-year famine known as the Beminitiya Seya and simultaneous foreign invasions. Monks were dying of starvation, and the monastic community was scattered. The elders realized that if the few monks who had memorized specific texts died, those teachings would be lost to humanity.

The Council at Aluvihara

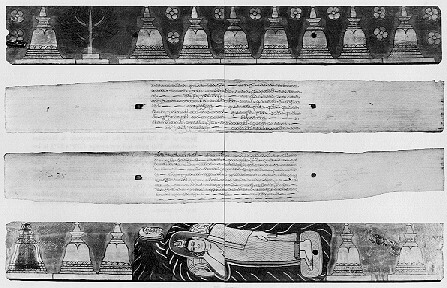

To prevent this catastrophe, a council of 500 scholarly monks gathered at the Aluvihara Rock Cave Temple in Matale. In a monumental effort that lasted for months, they inscribed the entire Tripitaka (the three baskets of the Canon: Vinaya, Sutta, and Abhidhamma) onto prepared palm leaves (ola leaves).

A Gift to the World

This event was a watershed moment in religious history. It transformed Buddhism from an oral tradition into a literary one. The Pali Canon recorded at Aluvihara became the standard text for Theravada Buddhism, eventually spreading to Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, and Laos. Today, it remains the most complete surviving record of the Buddha’s original teachings.