In the quiet halls of the Mahavihara monastery in ancient Anuradhapura, a Buddhist monk named Mahanama set out to accomplish something extraordinary in the 5th or 6th century CE. Armed with palm leaves, a sharp stylus, and centuries of oral tradition, he would create one of the most remarkable historical documents the world has ever known—the Mahavamsa, or “Great Chronicle,” a meticulously detailed account of Sri Lankan history that would span over two millennia and earn recognition from UNESCO as a world documentary heritage in 2023.

The Birth of a Chronicle

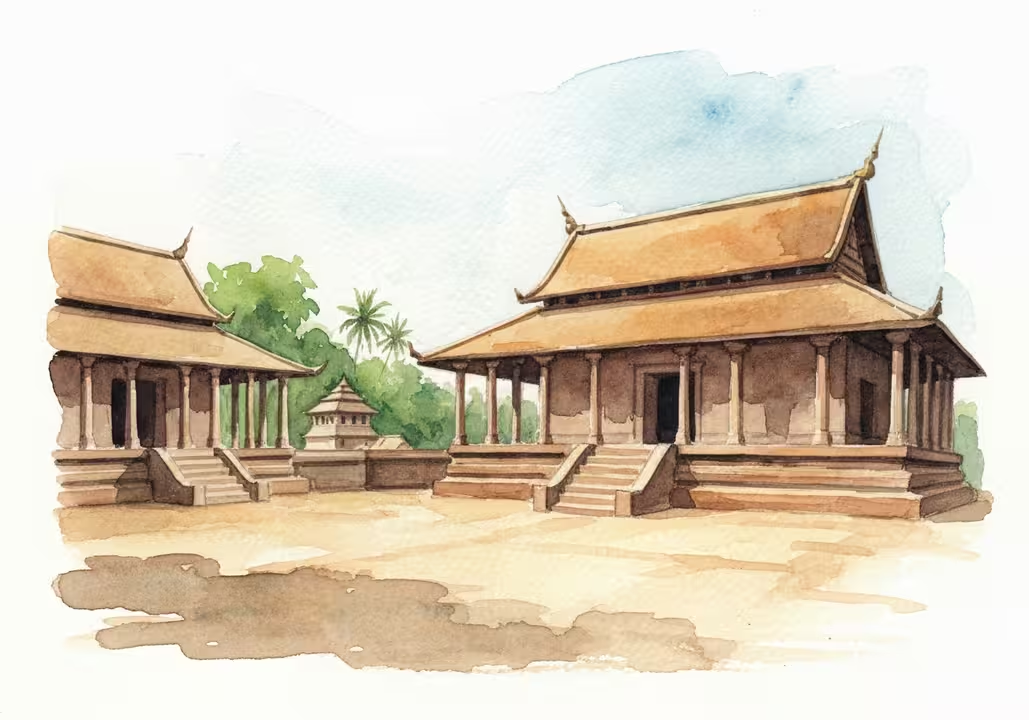

The Mahavamsa did not emerge from a vacuum. By the time Mahanama sat down to compose this epic work at the Mahavihara monastery—the great stronghold of Theravada Buddhism founded by King Devanampiya Tissa in the 3rd century BCE—Sri Lankan monks had already been preserving history through oral traditions for centuries. The Buddhist tradition of careful record-keeping had deep roots on the island, where monks meticulously memorized and passed down accounts of kings, battles, religious developments, and cultural achievements from generation to generation.

Mahanama drew upon two primary sources for his work. The first was the Dipavamsa, a “cruder” but earlier chronicle from the 4th century CE that served as the first written attempt to record Sri Lankan history. The second source was the rich oral tradition maintained by Buddhist monks, stories and accounts handed down with remarkable precision through centuries of careful memorization. This combination of written precedent and oral tradition allowed Mahanama to create a work of unprecedented scope and detail.

Written in Pali—the sacred language of Theravada Buddhism—the Mahavamsa was composed not as a dry historical record but as an epic poem. Its verses chronicled Sri Lankan history from the legendary arrival of Prince Vijaya from India in the 6th century BCE through the early 4th century CE, covering the reign of King Mahasena of Anuradhapura. The work’s elegant verse structure was no accident; it was designed for memorization, ensuring that even if the physical manuscripts were lost, the chronicle could survive in human memory.

The Sacred Art of Palm Leaf Writing

To understand the Mahavamsa’s creation, one must understand the extraordinary process of ola, or palm leaf manuscript writing, a tradition that began in Sri Lanka in the 3rd century BCE and continued until the 18th century when Dutch colonizers introduced the printing press.

The leaves came from two species of palm trees—the Corypha umbraculifera (ola) and Borassus umbraculifera. Harvesting and preparing these leaves was an art form in itself. After cutting leaves from the tree, monks would separate the segments and remove the middle rib. The leaves were then rolled, dipped in water, and boiled gently with unripe papaya pulp and pineapple leaves—a process that softened the fibers and made them flexible.

After boiling, the leaves were left to dry in the sun for several days before being stored in kitchens within the stove hood, where wood smoke would penetrate the leaves, adding to their durability. The final step involved polishing each leaf by running it back and forth on a smooth cylinder of areca palm tree until a perfectly smooth writing surface was obtained.

The actual writing process required years of training. Scribes learned to trace letters on the cured palm leaf and incise them with a sharp steel-pointed stylus, applying even pressure so that the script would be uniformly deep and bold. Each ola leaf manuscript page measured approximately eighteen inches long and an inch and a half high—a format that would define Sri Lankan literature for over two thousand years.

But the engraved letters were nearly invisible on the pale leaf surface. To make them readable, scribes employed an ingenious blackening technique. They created a special ink by combining fine charcoal dust—often from burned cotton plant leaves—with an alluvial resin. This mixture was heated until it produced a black resinous oil. The scribe would then rub this oil over the entire manuscript page with a cloth, coating it completely in black. When the excess was wiped away, the ink remained only in the incised grooves, creating crisp, readable letters that would last for centuries.

Completing a single leaf took approximately two days of meticulous work. The finished leaves were bound together between decorative wooden covers, often made of ebony and adorned with brass or silver, creating volumes that were both functional and beautiful.

A Living Chronicle Across Centuries

What makes the Mahavamsa truly exceptional is that it did not end with Mahanama. The chronicle became a living document, continuously updated by successive generations of Buddhist monks who saw it as their sacred duty to maintain this historical record for posterity.

The Culavamsa, or “Lesser Chronicle,” extended the Mahavamsa from where it left off in the 4th century CE all the way to 1815, when the British took control of Sri Lanka. Unlike the original Mahavamsa, which was composed by a single author, the Culavamsa was written by at least five different authors across many centuries, each adding their chapters to the great chronicle. The monk Dhammakitti wrote the first major portion, while Tibbotuvave Sumangala Thera compiled the section dealing with later medieval kings. Hikkaduve Siri Sumangala continued the chronicle up to 1815. Even in 1935, the monk Yagirala Pannananda extended the chronicle further in Sinhala, creating what is known as Mahavamsa Part III.

This unbroken chain of chronicling, maintained by Buddhist monks over more than two thousand years, created one of the world’s longest continuous historical records—a feat unmatched in South Asia and rare anywhere in the world.

The Battle Against Time

Preserving the Mahavamsa and other palm leaf manuscripts proved to be an ongoing battle against the very climate that sustained the palm trees. The tropical heat and humidity of Sri Lanka—perfect for growing palm trees—was devastating to palm leaf manuscripts. Insects, fungi, and moisture constantly threatened to destroy these fragile records.

Ancient Sri Lankan monks developed preservation techniques to combat these threats. They used special oils made from the distilled resins of Vateria copallifera trees, which made the leaves more flexible while serving as a fungicide and insecticide. Manuscripts were regularly treated with these protective oils and stored in special conditions to maximize their survival.

Despite these efforts, the climate took its toll. Apart from brief quotations in inscriptions and a two-page fragment from the 8th or 9th century found in Nepal, the oldest surviving Mahavamsa manuscripts date only from the late 15th century. The original manuscripts created by Mahanama and his immediate successors have long since turned to dust. The chronicle survived only because monks recognized that preservation required continuous copying. Generation after generation, scribes laboriously reproduced the text on fresh palm leaves, ensuring that even as individual manuscripts deteriorated, the chronicle itself remained intact.

The great chronicle Mahavamsa exists today in several palm leaf manuscript copies, preserved in temples across Sri Lanka and in international collections. In moments of crisis, monks went to extraordinary lengths to protect these manuscripts. When the missing commentary (tika) to the Mahavamsa was desperately needed, searchers combed old Buddhist temples—the only possible repositories of such documents—and finally found it at Mulgirigalla temple near Tangalle, a monastery founded 150 years before Christ.

A Chronicle of Global Significance

The Mahavamsa’s importance extends far beyond Sri Lankan shores. It stands as one of the most crucial historical sources in all of South Asia, containing invaluable information about the life of the Buddha, the great Indian Emperor Ashoka, and the rise of Buddhism as a world religion. The chronicle played a significant role in popularizing Buddhism throughout Southeast Asia and contributed singularly to establishing Emperor Ashoka’s place in Indian history.

The authenticity of the Mahavamsa’s historical accounts has been repeatedly confirmed through archaeological research in both Sri Lanka and India. When archaeologists excavate ancient sites mentioned in the chronicle, they consistently find that the Mahavamsa’s descriptions align with physical evidence. This verification has established the chronicle as a reliable historical source, not merely a religious text.

Beyond its historical value, the Mahavamsa represents the first mature historiographic tradition in South Asia, presenting history in chronological order with careful attention to dates, dynasties, and cause-and-effect relationships. Its influence spread across Buddhist Asia, with manuscripts and translations appearing in multiple Southeast Asian and European languages.

In recognition of its immense historical, cultural, literary, linguistic, and scholarly value, UNESCO inscribed the Mahavamsa on the Memory of the World International Register in 2023, placing it among 64 new items of globally important documentary heritage. This recognition affirms what generations of scholars have known: the Mahavamsa is not just Sri Lanka’s chronicle—it is a treasure of human civilization.

The Legacy of the Chroniclers

The story of the Mahavamsa is ultimately a story of dedication. For over 1,500 years, Buddhist monks maintained an unbroken chain of historical record-keeping, working in monastery scriptoriums, carefully engraving letters on palm leaves, mixing blackening resins, and copying aging manuscripts onto fresh leaves. They did this work not for fame or fortune, but because they understood that preserving history was a sacred trust.

Today, as palm leaf manuscripts face new threats from negligence, political unrest, and lack of awareness, efforts to digitize and preserve these documents have become crucial. Projects now work to catalogue and protect the thousands of palm leaf manuscripts scattered across Sri Lanka, ensuring that this ancient knowledge survives into the digital age.

The Mahavamsa stands as a testament to what human dedication can achieve. In an age without printing presses, in a climate hostile to preservation, using materials that deteriorate within decades, ancient Sri Lankan monks created a historical record that has survived for over 1,500 years. Their chronicle continues to enlighten us about the past, reminding us that the careful preservation of history is one of humanity’s most noble endeavors.