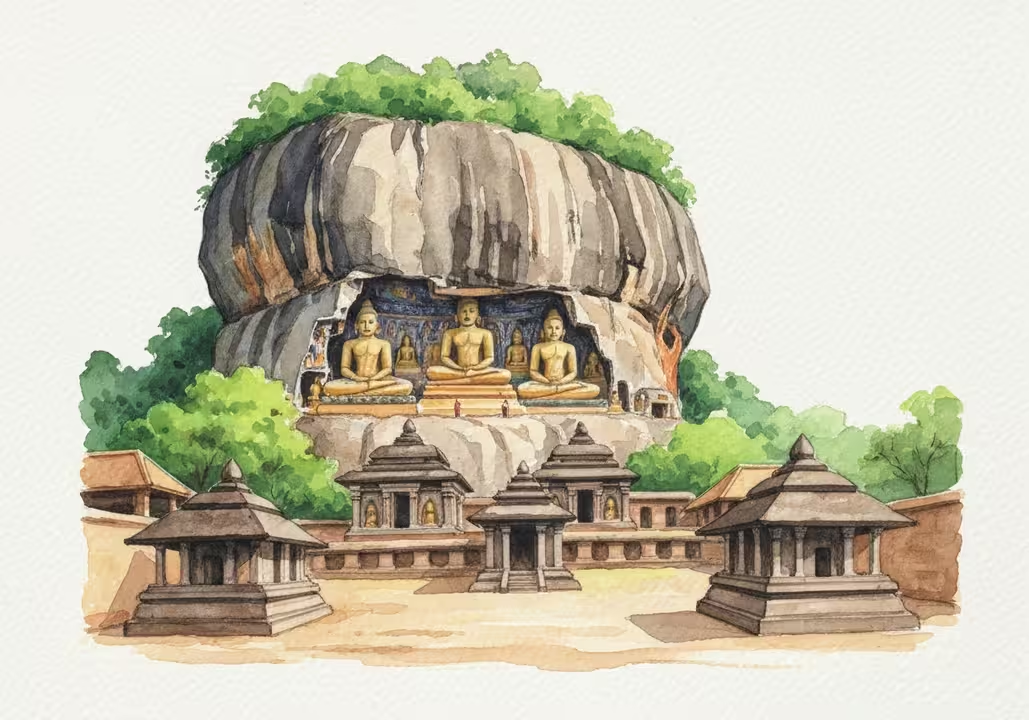

High above the plains of central Sri Lanka, a massive granite outcrop rises 160 meters into the sky. Within its sheltering embrace lie five caves that have witnessed over two millennia of continuous Buddhist devotion—making Dambulla Cave Temple not merely an ancient monument, but a living testament to faith that has transcended centuries.

A King’s Refuge, A Nation’s Sanctuary

The story of Dambulla’s transformation from natural shelter to sacred sanctuary begins with desperation and ends with gratitude. In the first century BCE, King Valagamba of Anuradhapura found himself fleeing for his life. South Indian invaders had seized his throne, forcing the monarch into a fifteen-year exile that would forever change the face of Sri Lankan religious architecture.

During those years of displacement, these natural caves became his refuge. Buddhist monks had already made these chambers their meditation retreats as early as the third and second centuries BCE, establishing what was then one of the largest and most important monasteries in the region. The king sheltered among them, sharing their austere existence, contemplating both loss and hope beneath ceilings of living rock.

When Valagamba finally reclaimed his kingdom, he did not forget the caves that had protected him. In an act of profound thanksgiving, he transformed these humble shelters into a magnificent rock temple. A first-century Brahmi inscription carved over the entrance to the first cave records this founding moment—one of the earliest written testimonies to the temple’s sacred origins.

Five Chambers of Wonder

Each of Dambulla’s five caves possesses its own character, its own story written in stone and pigment.

Devaraja Lena, the Cave of the Divine King, greets pilgrims first. Here, a colossal reclining Buddha stretches fourteen meters, carved directly from the living rock. The statue’s serene face has been repainted countless times across the centuries, most recently in the twentieth century, each restoration a fresh declaration of faith. At the Buddha’s feet stands Ananda, his beloved disciple, while at his head the Hindu deity Vishnu keeps eternal watch—a reminder of the syncretic spirituality that has long characterized Sri Lankan Buddhism.

The second cave, Maharaja Lena or the Cave of the Great Kings, overwhelms with its scale and splendor. Stretching over fifty-two meters, it houses sixteen standing and forty seated Buddha figures. But the cave contains more than Buddhist imagery alone. Here, stone preserves the memory of royal patronage: statues of King Valagamba himself, who honored the monastery in gratitude, and King Nissanka Malla of Polonnaruwa, who in 1190 CE gilded the caves and added seventy more Buddha statues. Between the statues, a natural spring drips from a crack in the ceiling, its water believed to possess healing powers. The 18th-century tempera paintings that dance across the ceiling tell the Buddha’s story in vivid color—from Queen Mahamaya’s prophetic dream to the demon Mara’s failed temptations.

Maha Alut Viharaya, the Great New Temple, became the canvas for Kandyan artistic genius during the reign of King Kirti Sri Rajasinha (1747-1782), that famous Buddhist revivalist who reinvigorated monastic life across the island. The cave’s ten-meter-high sloping ceiling creates the illusion of an enormous tent sheltering over fifty Buddhas. Here, the paintings reach their zenith—stunning explosions of yellow and red that illuminate ancient frescoes depicting not just the Buddha’s life, but the future: Maitreya, the Buddha yet to come, preaching to stern followers and magnificently decorated gods in the Tusita paradise.

The fourth cave, Pachima Viharaya (Western Temple), though smaller, carries its own treasure: a small dagoba said to contain the jewellery of Queen Somawati, consort to King Valagamba. It is a reliquary within a reliquary, a reminder that these caves preserve not just art and architecture, but the intimate objects of devotion from centuries past.

The fifth and final cave, Devana Alut Viharaya (Second New Temple), breaks from tradition. Unlike its companions, where Buddhas emerge from solid granite, this cave’s eleven statues are fashioned from brick and plaster. Originally a meditation chamber for monks seeking solitude, it was later repurposed as a shrine—evidence of the complex’s organic growth across the ages.

The Art of Devotion

What makes Dambulla extraordinary is not merely its age or scale, but the artistic achievement preserved within its stone chambers. Over 2,100 square meters of mural paintings cover the walls and ceilings—one cave alone contains more than 1,500 images of the Buddha. These paintings depict Jataka tales of the Buddha’s previous lives and chronicle significant moments in Sri Lankan history, including the legendary arrival of the first Sinhalese people to the island.

The technique behind these masterpieces reveals the sophisticated knowledge of 18th-century Kandyan artists, particularly those from the hamlet of Nilagama who became hereditary temple painters. They worked in tempera on dry plaster—a demanding medium requiring precision and speed. The plaster itself was an alchemical creation: white ceramic clay mixed with slime extracted from para fruit peel, rice gruel, embryo coconut, and various barks, all bound together with wild bees’ honey.

The pigments came entirely from nature. Red flowed from Ixora flowers and red clay. Yellow emerged from mud limestone and Clusiaciae juice. Blue derived from Fabaceae plants. Black required the most elaborate preparation: resin from yahakalu and dummala trees mixed with aged jak tree gum, ground together, roasted over fire until the sooty deposit could be emulsified with woodapple latex—which also served as the binding medium for all vegetable dyes except yellow.

The Kandyan style employed a deliberately limited palette—red, black, yellow, and white—yet created scenes of extraordinary vitality and emotion. When UNESCO and Sri Lankan authorities undertook major conservation between 1982 and 1996, they focused primarily on preserving these 18th-century schemes, which represent approximately eighty percent of the surviving paintings.

An Unbroken Thread

What makes Dambulla truly remarkable among the world’s religious monuments is its continuity. This is not a ruin visited by tourists and studied by archaeologists. For twenty-two centuries, pilgrims have climbed the stone steps to these caves. Monks have meditated in their cool shadows. Incense has risen before the Buddhas’ serene faces. Prayers have echoed off ancient rock.

The caves underwent renovation and refurbishment throughout history—under Anuradhapura kings, Polonnaruwa rulers, and Kandyan monarchs—but each transformation built upon rather than replaced what came before. The site embodies what scholars call “living heritage”: a place where ancient traditions continue unbroken into the present.

In 1991, UNESCO recognized this extraordinary achievement by designating Dambulla as a World Heritage Site. The citation praised not merely the complex’s artistic and archaeological significance, but its demonstration of continuous Buddhist ritual practice and pilgrimage spanning more than two millennia.

Where Faith Transforms Stone

Today, as sunlight streams through cave entrances, illuminating painted ceilings that glow like illuminated manuscripts, Dambulla continues to fulfill the purpose for which King Valagamba transformed it over two thousand years ago. It remains a sanctuary—not just for Buddhist devotees, but for anyone seeking to understand how faith, art, and time can collaborate to create something transcendent.

The Buddha images at Dambulla—from the fifteen-meter reclining giant to the smallest plaster figure—do not simply represent religious iconography. They embody the accumulated devotion of countless artisans, monks, kings, and pilgrims who across centuries chose to pour their resources, skills, and prayers into transforming cold rock into warm sanctuary.

In an age when so much is fleeting, Dambulla offers a different testimony: to permanence through impermanence, to continuity through change, to the human capacity to create beauty that outlasts empires and ideologies. The caves that once sheltered a fugitive king now shelter something more precious—the living memory of devotion itself, painted and carved and prayed into existence, renewed with each generation yet fundamentally unchanged.

The spring still drips in Cave Two. Pilgrims still climb the ancient steps. Incense still rises before serene stone faces. And Dambulla, where rock becomes prayer, continues its quiet vigil over the plains below—a sacred space where twenty-two centuries feel less like a vast expanse of time and more like a single, sustained act of worship.