For more than two millennia, the waters off Colombo’s coast have witnessed an endless procession of vessels—from Roman galleys laden with gold seeking Ceylon’s legendary cinnamon, to massive container ships that today make the Port of Colombo the busiest transshipment hub in South Asia. This is the remarkable story of how a modest natural anchorage transformed into a modern maritime powerhouse that moves over 7.7 million containers annually.

The Ancient Harbor: A Crossroads of Civilizations

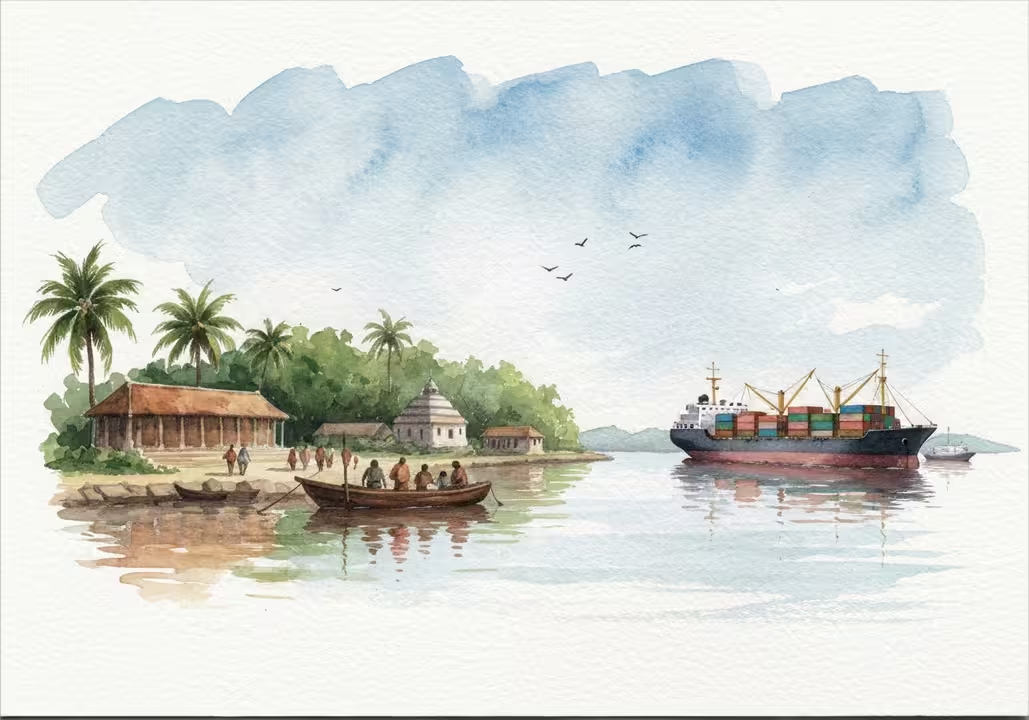

Long before European ships appeared on the horizon, Colombo’s sheltered waters were already known to the great maritime traders of the ancient world. More than 2,000 years ago, Roman merchants navigated the monsoon winds to reach Ceylon’s shores, exchanging gold and glassware for the island’s precious spices and gemstones. Arab dhows and Chinese junks followed similar routes, drawn by the island’s strategic position on the Maritime Silk Road.

By the 8th century, Arab Muslim traders had established permanent settlements in Colombo, transforming it into a thriving commercial base. The harbor served as a vital link connecting the Arabian Sea with the Bay of Bengal, a natural stopping point where merchants could refresh their crews, repair their vessels, and exchange goods from distant lands.

Yet Colombo was not always the island’s premier port. In the centuries preceding the thirteenth century, Mahatittha near Mannar on the northwestern coast held that distinction, serving as the great port facing the Arabian Sea. The coastal settlement of Mantai flourished as a maritime trade center from the 5th century BCE through the 13th century CE. But Colombo’s deeper waters and more central location would eventually prove decisive in securing its prominence.

The Colonial Transformation: Fortifications and Monopolies

The arrival of Portuguese navigator Lourenço de Almeida in 1505 marked the beginning of a new chapter in Colombo’s maritime history. The Portuguese, recognizing the harbor’s commercial and strategic value, expelled the Muslim merchants who had long dominated trade. By 1517, they began constructing a fort to protect their new possession, marking the first European attempt to transform the natural anchorage into a fortified colonial harbor.

Successive European powers would fight for control of this precious asset. The Dutch, after signing a treaty with King Rajasinghe II of Kandy in 1638 for monopoly over the island’s trade goods, laid siege to the Portuguese fort. In 1656, after a devastating siege that reduced the garrison to just 93 survivors, the Dutch took control. They expanded the fortifications, creating a well-defended harbor that would serve as the capital of the Dutch Maritime Provinces under the Dutch East India Company’s administration until 1796.

The British captured Colombo in 1796 and immediately recognized its potential. Unlike their predecessors who had prioritized military fortifications, the British envisioned something far more ambitious. They established Colombo as the capital of the new British Crown Colony of Ceylon and began planning civilian infrastructure that would lay the foundations for the modern port.

Breaking the Sea: The Age of Engineering Marvels

The true transformation of Colombo from a natural anchorage to a world-class artificial harbor began with a visionary proposal. In 1866, the Earl of Carnarvon suggested creating an artificial harbor to dramatically increase Ceylon’s shipping capacity. The idea captured the imagination of colonial administrators who recognized that expanding maritime trade was essential to the colony’s economic future.

In 1870, Governor Sir Hercules Robinson commissioned a feasibility study by Robert Townsend, the distinguished engineer who had designed Plymouth Breakwater. The report proved favorable. Two years later, in 1872, the legendary harbor engineer Sir John Coode drew up ambitious plans for a massive breakwater that would run north from Customs House Point at the southern entrance, enclosing 500 acres of sheltered moorings. The design also included land reclamation for a coal depot and extensive dredging to deepen the harbor floor.

Parliament approved the plans in 1873, and construction commenced in 1875. The engineering feat that followed was remarkable by any standard. John Kyle, appointed as Resident Executive Engineer, arrived in May 1873 to organize the enormous logistical operation. A quarry was opened at Mahara, eleven miles from Colombo, to supply the massive quantities of stone required. A blockyard was established at Galle Buck near the construction site. Most impressively, a dedicated railway line was constructed to transport stone from the quarry to the harbor—the first trainload of rubble arrived in October 1874.

The main engineering staff reached Ceylon in June 1874, bringing with them innovative construction methods. Two enormous steam-powered machines called Titans were employed to lay massive concrete blocks onto a bed of broken rubble stone, working five months each year when weather conditions permitted. Thousands of laborers toiled to build what would become one of the most significant infrastructure projects in colonial Ceylon.

When the South West Breakwater was finally completed in 1885, it stood as a monument to Victorian engineering ambition. The massive stone barrier tamed the Indian Ocean’s waves, creating a safe, sheltered harbor that could accommodate the increasing size and number of vessels calling at the colony.

The Golden Age: “Clapham Junction of the East”

The impact of the breakwater was transformative. With further improvements including extensive dredging and new berthing facilities, Colombo Port entered its golden age. By 1910, it had earned the nickname “Clapham Junction of the East”—a reference to London’s busiest railway interchange—and achieved the remarkable distinction of being the seventh busiest port globally by tonnage, surpassing even Liverpool and Singapore.

This prominence was no accident. Colombo’s strategic position on the vital shipping route between the Suez Canal and Australia made it an essential stopping point for vessels crossing the Indian Ocean. The harbor served as a major entrepôt for the entire Indian subcontinent, with goods flowing through its wharves from across South and Southeast Asia. Coal bunkers supplied fuel for the steam ships that plied these waters, while repair facilities kept vessels seaworthy on their long voyages.

In 1912, the port was officially converted into a fully sheltered harbor, and the following year, the Colombo Port Commission was established to manage the growing complexity of port operations. The harbor had become not merely a colonial asset but a vital node in the global network of trade and communication that connected empires and continents.

The Container Revolution: Adapting to Modern Maritime Trade

Following independence in 1948, management of the port eventually transitioned to Sri Lankan authorities. The Sri Lanka Ports Authority (SLPA) was constituted under Act No. 15 of 1979, merging the Colombo Port Commission with existing statutory corporations. The new organization took charge on August 1, 1979, at a pivotal moment in global shipping history.

The 1980s proved to be the most dynamic decade in Colombo Port’s modern history. Global maritime trade was undergoing a revolution as containerization transformed how cargo was handled. No longer would longshoremen spend days manually loading and unloading individual crates and barrels. Standardized containers could be efficiently transferred between ships, trains, and trucks using specialized cranes, dramatically reducing costs and turnaround times.

Recognizing that adapting to this revolution was essential for survival, SLPA embarked on a major transformation program. With international yen loans from Japan, the port constructed its first dedicated container facilities. The Jaya Container Terminal I (JCT I) opened in 1985, featuring a 300-meter berth with a water depth of 12 meters. JCT II followed in 1987, adding another 332 meters of berth with 13-meter depth. Transfer cranes began operating, and by the end of the decade, Colombo had established itself as a fully equipped container terminal.

The transformation continued through the 1990s with three additional berths. In the late 1990s, a crucial decision would secure Colombo’s future: the introduction of private sector operators. This move brought international expertise and investment, consolidating Colombo’s position as the major regional hub port for transshipment cargo in the Indian Ocean.

The Modern Giant: A 21st Century Transshipment Hub

The 21st century has witnessed Colombo Port’s emergence as one of the world’s elite maritime facilities. In 2013, the Colombo South Container Terminal (CICT) opened its doors—a state-of-the-art facility with 2.4 million TEU (twenty-foot equivalent unit) capacity, built through a joint venture between China Merchants Holdings and SLPA under a 35-year build-operate-transfer agreement.

The port’s strategic advantages have only grown more pronounced in the era of globalization. As the largest and busiest port in the Indian Ocean, Colombo’s position allows it to serve as a critical transshipment hub where cargo is transferred between vessels traveling different routes. Large mother ships from Europe and East Asia discharge containers destined for smaller Indian Ocean ports, which are then loaded onto feeder vessels for final delivery.

The numbers tell the story of remarkable growth. By 2024, Colombo Port handled a record 7.78 million TEUs in total container throughput, representing a 12.1 percent increase from the previous year. Transshipment volumes reached an unprecedented 6.31 million TEUs, accounting for 81 percent of total throughput. These achievements earned Colombo recognition as the best-performing port globally for the first quarter of 2024, with a growth rate of 23.6 percent—a remarkable recovery from the economic challenges Sri Lanka faced in preceding years.

Today, the Port of Colombo ranks first in South Asia and the Indian sub-continent, third among all ports in the Indian Ocean Rim, and twenty-second among 370 ports worldwide. The Colombo International Container Terminals operates the only deep-water terminal in South Asia capable of handling the largest container vessels afloat.

New investments continue to expand capacity. The West Container Terminal, a $700 million project jointly developed by Adani Ports, John Keells Holdings, and SLPA with $553 million in funding from the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, is scheduled to become operational in 2025. The East Container Terminal’s second phase, initiated by SLPA in 2022, will add further capacity. Together, these developments are projected to increase the port’s total capacity to 15 million TEUs by 2026.

Economic Engine of a Nation

Beyond the statistics and infrastructure, Colombo Port serves as a vital economic engine for Sri Lanka. The port generates substantial foreign exchange through transshipment operations, where international shipping lines pay fees for using Colombo’s facilities and services. It creates thousands of direct jobs and supports numerous ancillary industries—ship chandlery, bunkering, logistics, warehousing, and financial services that cluster around major port facilities.

An efficient, competitive port reduces transportation costs for Sri Lankan exporters, making their products more competitive in global markets. It attracts foreign investment by ensuring that manufacturers can reliably move goods to international markets. The skills developed in port operations, logistics management, and maritime services contribute to the nation’s human capital development.

The journey from ancient anchorage to modern marvel spans more than two millennia, but the transformation has been most dramatic over the past 150 years. From the bold engineering vision that broke the sea with massive breakwaters in the 1870s, through the containerization revolution of the 1980s, to today’s high-tech automated terminals, Colombo Port has continuously adapted to remain relevant in an ever-changing global economy.

As massive container ships glide past the historic breakwaters that Victorian engineers laboriously constructed stone by stone, they carry forward a legacy of commerce and connection that stretches back to the Roman traders who first recognized Ceylon’s strategic position at the heart of the Indian Ocean. The Port of Colombo stands not merely as infrastructure, but as testament to human ingenuity, international cooperation, and the enduring importance of maritime trade in connecting civilizations and driving economic prosperity.