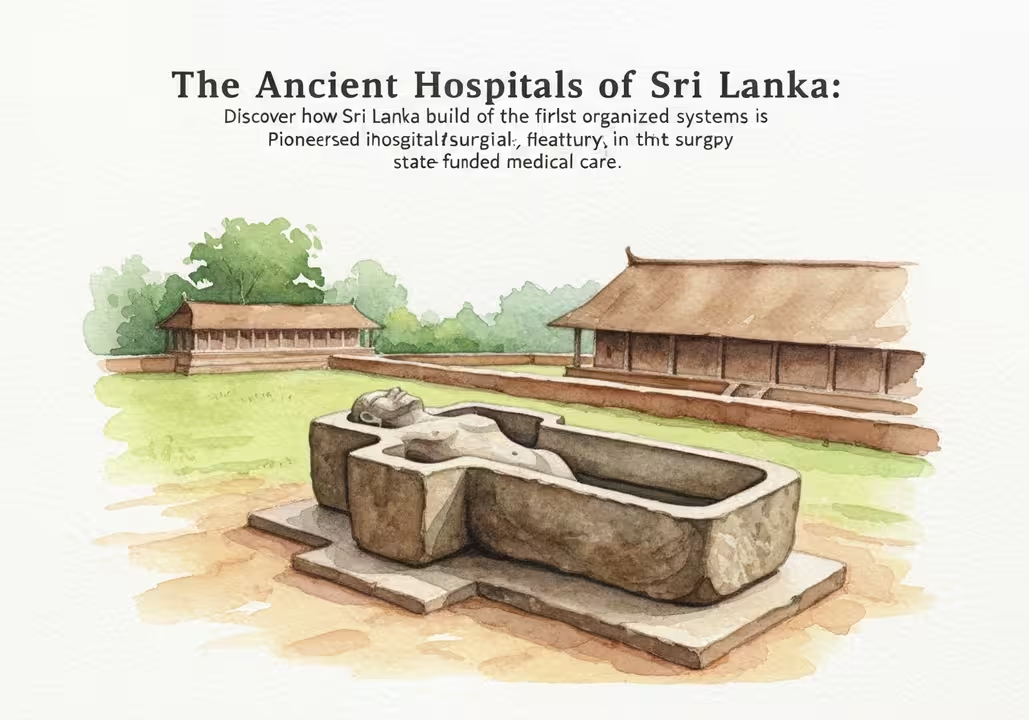

In the verdant mountains of Mihintale, carved from a single block of granite, lies a stone trough shaped like a human body. For over a thousand years, this extraordinary artifact has stood as silent testimony to one of history’s most remarkable medical innovations. This is the beheth oruwa, a medicinal immersion bath that was once filled with healing oils and herbal extracts, used to treat patients suffering from rheumatism, skin diseases, and even snake bites. It represents just one element of an ancient healthcare system so advanced that it challenges our assumptions about medieval medicine.

The Mihintale Hospital, established in the 9th century CE by King Sena II (851-885 CE), holds a unique distinction in medical history. According to scholar Heinz E. Müller-Dietz and recognized by UNESCO’s Silk Roads Programme, it may be the oldest hospital in the world for which archaeological evidence exists. But this remarkable institution was not an isolated achievement—it was part of a sophisticated network of hospitals that flourished across ancient Sri Lanka for over a millennium.

The Birth of Organized Healthcare

The story of Sri Lankan hospitals begins even earlier than Mihintale. According to the Mahavamsa, the great chronicle of Sri Lankan history, King Pandukabhaya established lying-in homes and hospitals in various parts of the country after fortifying his capital at Anuradhapura in the 4th century BCE. This makes Sri Lanka one of the earliest civilizations to establish organized medical facilities, predating most European hospitals by centuries.

However, it was King Buddhadasa (340-368 CE) who truly revolutionized healthcare on the island. Known as the “Physician King,” Buddhadasa was no mere patron of medicine—he was an accomplished practitioner himself. The Mahavamsa describes him as “a mine of virtues, as the sea is of jewels,” and records that he was adept in general medicine, surgery, midwifery, and even veterinary medicine.

King Buddhadasa’s medical achievements were extraordinary for his time. Historical records document how he performed a cephalotomy—a brain surgery involving opening the skull—to cure a patient suffering from severe headaches due to a cerebral cyst. He successfully performed a cesarean section to deliver a child, and the chronicles even mention his surgical removal of a lump from a snake’s belly. Such was his dedication to his medical practice that he constantly carried a set of surgical instruments with him on his journeys.

But Buddhadasa’s most enduring legacy was not his personal medical skill—it was his vision of universal healthcare. He established hospitals in every village across the island and appointed physicians to staff them, compensating them with land grants. He created a healthcare system with one hospital for every ten villages, funded by taxes on the revenue from fields in those villages. This represents one of the earliest examples of state-funded healthcare in world history, a concept that would not be widely adopted in Europe until the 20th century.

Buddhadasa was also Sri Lanka’s first medical author, composing a comprehensive medical text called Sarartha Sangraha in Sanskrit. This compendium contained detailed instructions on clinical reasoning, therapeutics, and pharmacopoeia. It gave prominent attention to diseases including tuberculosis, snake bites, skin conditions such as psoriasis and leprosy, and even psychiatric disorders—demonstrating a remarkably broad understanding of medicine.

The Monastic Hospital System

As Buddhism flourished in Sri Lanka, hospitals became integral to the monastic complexes that dotted the island. Buddhist monks studied medicine and healing became part of their religious practice, a tradition that continues to the present day. These monastic hospitals were attached to larger monasteries, functioned semi-autonomously, and focused primarily on caring for sick monks, though they also served the wider population.

Major hospital complexes have been identified at Mihintale, Polonnaruwa, Medirigiriya, Dighavapi, Thuparamaya, and within the Maha Viharaya and Alahana Pirivena monastic complexes. King Kassapa IV (898-914 CE) built hospitals in Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa specifically for combating the upasagga disease. Later, King Parakramabahu I (1153-1186 CE) constructed the impressive hospital complex at the Alahana Parivena in Polonnaruwa.

Archaeological excavations at these sites have revealed sophisticated architectural designs that demonstrate advanced understanding of healthcare requirements. The hospitals were strategically located on easily accessible plains and were surrounded by walls to isolate them from other monastic buildings—an early form of quarantine protocol. The buildings were designed to allow maximum ventilation, crucial for patient recovery and infection control.

Architectural Sophistication

The layout of these ancient hospitals reveals careful planning and specialized functions. The restored Mihintale Hospital was a substantial rectangular building measuring 68.6 meters by 38.1 meters. According to the archaeological evidence, it comprised 31 rooms arranged on a high platform. The complex included distinctive features such as consulting rooms, rooms for hot water baths, an outer court, an inner verandah, a courtyard, a shrine room, and the specialized room for the medicinal trough.

The outer court housed rooms for the preparation and storage of medicines as well as facilities for hot water baths. The inner areas contained patient rooms and treatment facilities. Remarkably, some hospitals even had lavatories inside the building—an important sanitary feature rarely found in medieval structures elsewhere.

The Polonnaruwa Hospital, though smaller at 44.8 meters in total length, displayed similar architectural sophistication. Restored by the Cultural Triangle project in 1982, its layout reveals the same careful attention to separating different medical functions—consultation, treatment, medicine preparation, and patient care.

The Stone Medicinal Troughs

Among the most distinctive and intriguing features of these ancient hospitals are the stone medicinal troughs, known in Sinhala as beheth oruwa. These remarkable objects were hewn from monolithic granite blocks, with both the interior cavity and the complete structure carved in the shape of a human body. The patient would climb into this stone bath to be immersed in medicinal oils for extended periods.

The first such trough was discovered near the ruins of Thuparama monastery by archaeologist H.C.P. Bell in 1896. Subsequently, similar troughs were found at Mihintale, Medirigiriya, Dighavapi, and Polonnaruwa. These troughs were used for immersion therapy to manage skin conditions, rheumatism, hemorrhoids, and notably, snake bites—one of the most common medical emergencies in tropical Sri Lanka.

This treatment method, documented in a Pali commentary from the 5th century CE and in two 13th-century Sri Lankan medical texts written by Buddhist monks, demonstrates the sophisticated understanding of dermatological and systemic treatments. The use of extended immersion in medicated oils mirrors treatments still used in Ayurvedic medicine today, suggesting an unbroken medical tradition spanning more than 1,500 years.

Medical Instruments and Pharmaceutical Evidence

Archaeological excavations at hospital sites have yielded remarkable evidence of the medical practices employed. At the Polonnaruwa hospital, excavators discovered medicine grinders, a pair of scissors, ceramic jars for storing medicines, and a hooked copper instrument likely used for incising abscesses. The diversity of surgical instruments found across various sites is impressive: probes, forceps, scalpels, lancets, spoons, and micro-balances for precisely measuring medicines.

At Medirigiriya, where a hospital flourished in the 9th century, excavations revealed stone medicine troughs and querns (stone grinding tools) for preparing medicines from herbs and minerals. This physical evidence confirms what historical texts tell us: that ancient Sri Lankan physicians practiced a sophisticated form of pharmacy, carefully preparing medicines from multiple ingredients in precise proportions.

Perhaps most intriguingly, excavations at the Polonnaruwa hospital site uncovered two blue glass flasks from Persia. This discovery provides tangible evidence of international medical trade along the maritime Silk Road. Sri Lanka occupied a strategic position at the crossroads of sea routes connecting the Mediterranean, Persia, India, China, and the Spice Islands of Indonesia. Medical knowledge, techniques, and pharmaceutical ingredients flowed along these routes just as surely as silk and spices did.

Persian merchants brought glass vessels, wine, and other goods to Sri Lankan ports. Chinese pottery and ceramics have been found alongside Persian artifacts at excavation sites. This international exchange of goods almost certainly included the exchange of medical knowledge. Sri Lankan physicians learned from Indian Ayurvedic traditions, absorbed techniques like acupuncture from Chinese medical practice, and likely shared their own innovations with traders and scholars from across the known world.

Herbal Medicine and Pharmacopoeia

The foundation of ancient Sri Lankan medicine was its sophisticated use of medicinal plants. The traditional medical system had been practiced on the island for more than 3,000 years, incorporating Ayurveda, Siddha, Unani, and the indigenous Deshiya Chikitsa system. The Ayurvedic system alone utilized approximately 2,000 different herbs.

Sri Lanka’s exceptional biodiversity supported this extensive pharmacopoeia. Modern surveys have identified 3,771 flowering plant species on the island, of which 1,430 possess medicinal properties. Remarkably, 174 of these medicinal plants (12%) are endemic to Sri Lanka, found nowhere else on Earth. Around 250 species were commonly used in traditional medicine.

Medicinal plant gardens were cultivated near hospitals and monasteries, serving as living pharmacies. The harvesting of medicinal plants was not merely a practical task but a ritualized practice. Healers performed special ceremonies before collecting plant materials, believing this preserved their therapeutic properties. Different parts of plants—leaves, roots, bark, flowers, and fruits—were collected at specific times and processed using traditional methods to create medicines.

The only medical text written in the Pali language, Bhesajja Manjusava, dates to the 13th century CE. Written by a monk named Atthadassi, it was specifically prescribed for monastic life and has been recognized as a national documentary heritage under UNESCO’s Memory of the World Programme. This text provides detailed instructions on diagnosing and treating various ailments using herbal remedies, highlighting the integration of Buddhist practice and medical care.

Medical Practices and Procedures

Written sources from the 5th century CE onward testify that Ayurvedic medicine, acupuncture, and surgery were all practiced in ancient Sri Lanka. The range of procedures performed was impressive for the medieval period. Beyond the dramatic surgeries performed by King Buddhadasa, regular surgical procedures included the treatment of wounds, the removal of foreign objects, the lancing of abscesses, and various obstetric procedures.

Medical education was formalized and rigorous. Physicians underwent extensive training, learning to diagnose diseases through examination of symptoms, pulses, and other physical signs. They studied the properties of hundreds of medicinal plants and learned complex formulations that combined multiple ingredients. Surgical training included the study of anatomy and the practice of delicate procedures requiring steady hands and keen eyesight.

Hospitals maintained different ranks of physicians, suggesting a hierarchical medical system with specialists in various fields. King Buddhadasa’s appointment of specialized physicians for horses, elephants, and soldiers indicates that veterinary medicine and military medicine were recognized as distinct specialties requiring dedicated practitioners.

A Legacy of Healing

The ancient hospital system of Sri Lanka represents one of the most remarkable achievements in the history of medicine. At a time when much of the world lacked organized healthcare, Sri Lankan kings were establishing networks of state-funded hospitals, training physicians, cultivating medicinal gardens, and performing sophisticated surgeries.

The stone troughs of Mihintale and Polonnaruwa still stand, weathered by centuries but intact—testimony to the vision of rulers who saw healthcare not as a privilege but as a right. The surgical instruments discovered in archaeological excavations speak to the skill and dedication of physicians who combined empirical observation with traditional knowledge. The Persian glass flasks remind us that medical knowledge has always transcended borders, spreading through trade routes and cultural exchange.

Today, Sri Lanka maintains a tradition of free healthcare that can trace its philosophical roots back to King Buddhadasa’s village hospital system. The island’s continued use of Ayurvedic medicine represents an unbroken chain of medical practice stretching back millennia. Modern research into Sri Lanka’s endemic medicinal plants is rediscovering therapeutic properties that ancient physicians knew well.

The ancient hospitals of Sri Lanka were more than buildings—they were institutions embodying a revolutionary idea: that healing the sick was a sacred duty, that medical care should be available to all regardless of wealth or status, and that the systematic study of medicine could alleviate human suffering. In stone and granite, in surgical instruments and medicinal troughs, in ruins scattered across the island, we can still read this ancient promise of healing—and recognize its continuing relevance to our modern world.